Article by Justin L Scharton, Independent Researcher

Last updated 12/19/2024

Terpenes

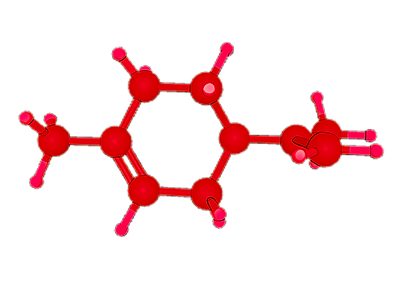

Terpenes are a diverse class of naturally occurring compounds responsible for many of the characteristic aromas and flavors found in plants, including cannabis. Terpenes have many different medicinal properties. Research suggests that these compounds may influence inflammation, stress, mood, and even fight against different cancers.

Understanding terpenes and their effects requires a foundation in organic chemistry. Terpenes often exist in multiple structural forms, known as isomers, that can display distinct behaviors in biological systems. Factors such as dextrorotatory (D) versus levorotatory (L) configurations, the Cahn-Ingold-Prelog (CIP) priority rules for naming stereocenters, and whether molecules exist as mirror images, or enantiomers, can all shape how a terpene interacts with receptors and enzymes in the human body. These differences are why seemingly similar compounds can produce very different physiological responses.

In this section, we will go over the basics of terpene chemistry and how to understand isomers, stereochemistry, molecular interactions, addressing online misinformation, and most importantly, their medicinal benefits. Click the terpenes below to jump to the section.

The basics of terpenes

Terpene Nomenclature and Prefixes

-alpha-Pinene.png)

Alpha-Pinene

Beta-Pinene

Dexter-Limonene

Terpenes such as alpha-pinene, beta-myrcene, and delta-3-carene use Greek letters to classify structural variations of the same chemical family. These prefixes indicate the position or configuration of certain chemical groups within the molecule that affect their chemical behavior and biological activity. For example, in the case of pinene, alpha-pinene and beta-pinene differ in the positioning of the double bond and the arrangement of their atoms. Other terpenes use a prefix that are often misinterpreted as a Greek letter, such as D-limonene often is misinterpreted as ‘Delta’ limonene, while in reality, ‘D’ stands for ‘Dexter’, indicating the direction in which the molecule rotates plane-polarized light, which is different from the structural variations denoted by Greek letters.

What is plane-polarized light?

D-Limonene (Dexter Limonene)

L-Limonene (Laevus Limonene)

Optically active compounds such as D-limonene (Dexter-limonene) and L-limonene (Laevus-limonene) will rotate the light when light passes through the compound, then into a polarimeter, and then the light exiting the polarimeter will be rotated to the right for “Dexter”, or to the left for “Laevus”. Because they interact with light, substances that can rotate plane-polarized light are said to be optically active. Those that rotate the plane clockwise (to the right) are said to be dextrorotatory (from the Latin dexter, "right"), or classified as +/- (such as +/- limonene). Limonene that rotates the plane counterclockwise (to the left) is levorotatory and is labeled as L-limonene or (-)- limonene. There is also a mix of both enantiomers called a racemic, such as combining D and L limonene that have the names Dipentene and (+/-)- limonene.

L-Limonene

D-Limonene

What are enantiomers?

D and L Limonene are enantiomers of each other. If one of the images are reversed in a mirror image, and superimposed on to each other, they will not match. With the superimposed image below, the structure does not quite match and the double bonds are in different places.

D-limonene in blue superimposed over a mirror image of L-limonene

L-limonene reversed into a mirror image

Enantiomers like D and L limonene can have different pharmacological effects, a different odor, and also affect different receptors and neurotransmitters.

Limonene

D-Limonene

+/- Limonene

L or S-Limonene

-/- Limonene

Dipentene

(+/-)- Limonene

Receptor interaction

+/- Limonene interacts with the adenosine A2A receptor,(89B) and an acetylcholinesterase inhibitor with an IC(50)=390.2 ± 30.0 (37E)

D-limonene (+/-) is a natural cyclic monoterpene. It has a pleasant lemon odor, and is a major component of citrus peels. It is sometimes labeled as R or 4R-Limonene.(86B) D-limonene is optically active when the plane-polarized light rotates to the right. This terpene is the one found in cannabis strains.

L-limonene (-/-) is found in Tanyosho pine (Pinus densiflora), Minthostachys mollis, and spearmint oil. This terpene is sometimes labeled as S-limonene or 4S-limonene.(87B)

(+/-)- Limonene aka Dipentene, is naturally found in some teas (Camellia sinensis), and is often used as a solvent for rosin, waxes, rubber; as a dispersing agent for oils, resins, paints, lacquers, varnishes, and in floor waxes and furniture polishes. Dipentene is a racemic mixture of limonene,(88B) meaning it has an equal mixture of both D and L-limonene. Dipentene is not optically active, meaning it will not cause a rotational change if this compound is used in a polarimeter.

Why are there different designations with D, L, R, and S limonene?

The “D” and “L” prefixes are described in more detail above here. They refer to the rotational direction of light when using an optically active compound with a polarimeter.(85B) The “R” means Rectus (Right) with the Cahn-Ingold-Prelog priority rules, and this indicates the absolute spatial arrangement of the molecule’s atoms. The “S” in S-limonene means Sinister (left) with these same rules of molecule arrangement.(85B)

The Cahn-Ingold-Prelog (CIP) priority rules determine the spatial arrangement of atoms around a chiral center, assigning configurations as R (Rectus, right) or S (Sinister, left). Unlike optical rotation, which is measured using a polarimeter, the CIP system assigns configurations based on the priority of atoms attached to the chiral center. To determine whether the configuration is R or S, arrange the molecule so that the lowest-priority group is positioned away from the viewer. If the sequence of remaining groups (from highest to lowest priority) follows a clockwise direction, the configuration is assigned as R; if it follows a counterclockwise direction, it is assigned as S. (85B)

The CIP rules are:

1. Higher Atomic number - Atoms directly attached to the chiral center are ranked by the atomic number (number of protons). The higher the atomic number, the higher the priority is. (85B)

2. First Point of Difference - If the atoms that are directly attached to the chiral center are the same, then we must look further along at each atom of the attached groups until a difference is found. The first point where there is a difference in the atomic number will determine the priority. (85B)

3. Multiple Bonds - Double and triple bonded atoms are looked at as if they are bonded to multiple single atoms. For example, a carbon double-bonded to another carbon is treated as if it is bonded to two additional carbons. (85B)

4. Isotopes - The atoms with a higher mass (more neutrons) will have a higher priority. (85B)

The system of classifying compounds like limonene that uses D or L is an older system that uses a polarimeter to see which direction the molecules will turn plane-polarized light. The CIP method is a systematic way to designate the spatial arrangement of atoms, using R (Rectus-right) which has the priority decreasing clockwise, and S (Sinister-left) which has the priority decreasing counterclockwise. D-limonene and R-limonene refer to the same terpene, while L-limonene and S-limonene are the same terpene.

The different limonenes have the same molecular formula C10H16 that represents the basic structure. The arrangement of the atoms determine the minor differences between the compounds, and they are labeled with a R or S as the prefix (or D and L for a different and older system). The arrangement difference influences how the molecules will interact differently with biological systems and receptors.

Limonene +/- Limonene -/- Limonene (+/-)-

Optically active terpenes, like limonene, are typically labeled as limonene +/-, limonene -/-, and limonene (+/-)-. This labeling is on medical and research websites such as the NIH and NLM. This labeling is to show that these compounds are optically active, and their optical rotation. It also helps to quickly understand the properties of limonene without having to remember all the other names that each one has; for example, limonene +/- has 124 different names that are listed on the pubchem website. Limonene +/- is the preferred name of D-limonene (R-limonene). Limonene -/- is the preferred name of L-limonene (S-limonene). Limonene (+/-)- is the preferred name of Dipentene.

Adenosine A2A receptor, Anxiety, and Parkinson’s Disease

Limonene directly binds to the adenosine A2A receptor.(89B) Limonene was also found to have anti-anxiety benefits, as it increases the amount of dopamine in the brain, and releases GABA.(90B) An adenosine A2A antagonist like istradefylline is used as adjunctive therapy in Parkinson’s disease with levodopa or decarboxylase inhibitors to reduce the OFF episodes or a wearing-off phenomenon,(91B) which is described as recurrence of motor and non-motor symptoms.(92B)

Possible Medication Interactions With Limonene

Limonene could interact with medications that increase or reduce dopamine. Here are symptoms that could possibly happen with limonene taken along with certain prescriptions, or worsen side effect of those prescriptions:

Overdoses from dopamine D2 agonists include dyskinesia, dystonia, hypotension, and dysrhythmias.(93B)

The dopamine agonist Cabergoline could have the side effects of nausea, vomiting, headache and dizziness.(94B)

Bromocriptine is another D2 agonist that could have the common side effects of nausea, vomiting, dizziness, hypotension, headache, and fatigue. More serious side effects could be psychosis, fibrosis (retroperitoneal, pleural, cardiac valve), and cardiovascular incidents (valvular damage, stroke, myocardial infarction).(95B)

Levodopa has the typical side effects of nausea, dizziness, headache, and somnolence. The elderly are more prone to the side effects of confusion, hallucinations, delusions, psychosis, and agitation.(96B) Limonene could increase some of these side effects.

Limonene (A2A agonist) could reduce the effectiveness of istradefylline (A2A antagonist) since they work completely opposite of each other.

Limonene against Colorectal Cancer

+/- Limonene (d-limonene) was found to induce cell death of human colon cancer cells through the mitochondrial death pathway, and suppression of the PI3K/Akt pathway. This terpene lowered the levels of p-Akt (Ser473), p-Akt (Thr308) and p-GSK-3β (Ser9), and caspase-3 and -9 and PARP were activated. Bax protein and cytosol cytochrome c from mitochondria were increased, and bcl-2 protein was reduced.(97B)

Limonene activates Caspase-3 and Caspase-9

Caspase-3 is the executioner in the process of programmed cell death (apoptosis). This enzyme dismantles the cell during apoptosis by cutting specific proteins that hold the cell together. This leads to the breakdown of the cell’s internal structures.(98B)

Caspase-9 can initiate apoptosis in cells, especially when they are in early development. When caspase-9 is activated, it starts a chain reaction that activates other caspases, including caspase-3. Part of their role is to prevent the spread of cancerous, faulty, or damaged cells to die before they can cause harm.(99B,1C)

Limonene suppresses the P13K/Akt pathway

The PI3K/Akt pathway plays a major role in many cellular functions throughout the body, including cell growth, survival, and metabolism. It’s often overactive in several types of cancer, making it a target for cancer therapy. Side effects from chemotherapeutic medications that inhibit this pathway can cause several side effects.(2C) For example:

1. GDC-0941 (Pictilisib) often causes side effects like mild to moderate nausea, fatigue, diarrhea, vomiting, changes in taste (dysgeusia), and loss of appetite. These effects arise because the drug not only targets cancer cells but can also affect healthy cells that rely on the PI3K/Akt pathway for normal functioning.(3C)

2. BKM120, another inhibitor, has been associated with rash, elevated blood sugar (hyperglycemia), diarrhea, loss of appetite, mood changes, nausea, itching (pruritus), and inflammation of the mucous membranes (mucositis). These symptoms reflect the role of the p13K/Akt pathway in regulating skin integrity, glucose metabolism, and neurological functions.(4C)

By targeting the PI3K/Akt pathway, these inhibitors can interfere with normal and essential cellular activities, leading to side effects that impact a patient’s quality of life and their willingness to use these medications. This is the challenge in designing medications that can selectively target cancerous cells without affecting healthy tissue.

Alpha-Pinene

+/- Alpha Pinene

-/- Alpha Pinene

(+/-)- Alpha Pinene

Receptor interaction

(+)-alpha-pinene and (-)-alpha-pinene are acetylcholinesterase inhibitors with an IC(50)=524.5 ± 42.4. (5C,37E) Since the racemic mixture (+/-)-alpha-pinene consists of an equal mix of these enantiomers, it can be inferred that it is also an acetylcholinesterase inhibitor.

(+/-)- alpha-Pinene is found in Eucalyptus, Mandarin, Coriander, Juniper Berry, Cannabis, Foeniculum vulgare Fruit, Camellia sinensis, and Callistemon citrinus. (6C)

(-)-alpha-Pinene is found in Camellia sinensis, Solanum tuberosum. (7C)

(+)-alpha-Pinene is found in Artemisia xerophytica, Salvia officinalis. (8C)

A-pinene - IC(50)=524.5 ± 42.4 mM as an acetylcholinesterase inhibitor (5C)

Acetylcholinesterase inhibitors are used in treating dementia, Alzheimer’s Disease, Cholinergic poisoning, and Myasthenia Gravis. They block the normal breakdown of acetylcholine into acetate and choline and increase both the levels and duration of actions of acetylcholine found in the central and peripheral nervous system. These medications will increase the parasympathetic response from the extra acetylcholine, which affects the vagus nerve. Overstimulation of the parasympathetic nervous system, such as increased hypermotility, hypersecretion, bradycardia, miosis, diarrhea, and hypotension. They should not be used in people with certain health problems such as bradycardia, and heart conditions like AV block. (10C)

Donepezil, rivastigmine and galantamine are common prescription acetylcholinesterase inhibitors.(11C) Combining these with a-pinene can worsen the risk of a slow heart rate (bradycardia), and other side effects mentioned in the last paragraph.

Alpha-Pinene for Neurodegeneration

Alpha Pinene was found to be a possible treatment for neurodegenerative diseases. In a study, rats were given beta-amyloid (Aβ) to induce oxidative/nitrosative stress, neuroinflammation, and molecular and behavioral changes. Then 50 mg/kg of a-pinene was injected intraperitoneally to find the benefits. Alpha Pinene reduced malondialdehyde, nitric oxide.(12C) Malondialdehyde is a marker of oxidative stress and the antioxidant status in cancerous patients.(13C)

Nitric oxide (NO) has important roles in intracellular signals in neurons, and regulating the blood flow to the brain. In some disease processes and in aging people, NO can turn harmful by reacting with superoxide anion to form peroxynitrite. Peroxynitrite is a gaseous compound that easily passes throughout the neuronal membranes to damage lipids, proteins, and nucleic acids. Nitro-tyrosines form when peroxynitrite reacts with proteins (nitro tyrosination), mainly with the phenolic ring of tyrosines. The accumulation of nitro-tyrosines contribute to the onset and progression of neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s.(14C)

A-Pinene can increase glutathione, and enhance catalase activity (12C)

Decreased levels of Glutathione (GSH), or in the ratio of GSH/glutathione disulfide, often occurs from an increased susceptibility to oxidative stress. That damage is involved in many disorders including cancer, diseases of aging, cystic fibrosis, cardiovascular, inflammation, immune disorders, metabolic problems, and neurodegenerative diseases. High levels of GSH can make some cancer cells more resistant to chemotherapy treatment.(15C)

Catalase is an antioxidant enzyme that reduces oxidative stress through breaking apart cellular hydrogen peroxide into water and oxygen. A deficiency or dysfunction of catalase has a role in many disorders including: diabetes mellitus, Alzheimer's disease, and Parkinson's disease.(16C)

Genetic disorders that result in people with little or no catalase activity can make them more prone to the development of diabetes through the cumulative oxidant damage of pancreatic beta-cells.(17C)

Alpha-Pinene for Alzheimer’s Disease

Beta-amyloid peptides can bind to catalase, and deactivate it. Hydrogen peroxide levels become increased due to the inactivation of catalase.(18C) Alpha-pinene strengthens the antioxidant system and prevents neuroinflammation in the hippocampus of rats receiving Aβ. It improves spatial learning and memory and reduces anxiety-like behavior in these animals. Consequently, alpha-pinene alleviates Aβ-induced oxidative/nitrosative stress, neuroinflammation, and behavioral deficits. It is probably a suitable candidate for the treatment of neurodegenerative diseases.(12C)

Alpha-Pinene for Parkinson’s Disease

Low catalase activity and high levels of hydrogen peroxide in Parkinson’s disease could be from a mutation in a gene that produces α-synuclein, creating a mutated version of α-synuclein. This mutated protein can reduce the expression and activity of catalase. It also can cause the dopamine produced in the cytoplasm of cells to auto-oxidize into hydrogen peroxide.(16C) Alpha-Pinene enhances catalase activity,(12C) which could help with Parkinson's Disease.

Nicotinic acetylcholine receptor α7 subunit

A-Pinene reduced the effects of the Amyloid-Beta-induced reduction of nicotinic acetylcholine receptor α7 subunit and brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) expression.(12C)

The nicotinic acetylcholine receptor α7 subunit is found throughout the body, and has large concentrations in the adrenal glands and the small intestine.(19C) This receptor is also a regulator of inflammation. Activating these receptors will turn on the “cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway” through reducing the release of macrophage TNF (Tumor-necrosis factor) from the vagus nerve, and reduce systemic inflammatory responses. As a comparison to other medical treatments, electrical stimulation of the vagus nerve inhibits TNF synthesis, while acetylcholine activation of the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor alpha7 subunit inhibits the release of macrophage TNF. Excessive inflammation and TNF can increase the death rate from endotoxemia, sepsis, rheumatoid arthritis and inflammatory bowel disease.(20C)

A-Pinene increases Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF)

Low levels of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) is associated with neuronal loss in Parkinson’s, Alzheimer's, Multiple Sclerosis, and Huntington’s Disease. Increased levels of BDNF can protect neuronal cells and pancreatic β cells, which can be helpful with Diabetes Type 2 as well as neurodegenerative disorders.(21C) A-Pinene increases BDNF.(45E)

Other cell signals affected by alpha-pinene

In the hippocampus, a-pinene reduced messenger RNA expression of tumor necrosis factor-α, interleukin-1β, interleukin-6, nuclear factor κB, and N-methyl- d-aspartate receptor subunits 2A and 2B.(12C)

Alpha-Pinene reduces NFkb (nuclear factor κB)

High levels of NFkb is associated with depression caused by chronic stress. Stress releases NFkb which stops neurogenesis in the adult hippocampus.(22C) Alpha-Pinene reduces NFkb.(12C)

Alpha-Pinene reduces TNF-a

Low levels of TNF-A showed an accelerated maturation of the dentate gyrus, and dendritic trees in CA1 and CA3 regions in a mouse brain. Increased expression of nerve growth factor (NGF), and improved behavioral tasks related to spatial memory are associated with reduced TNF-a.(23C) The increased NGF plays a critical role in protecting the development and survival of sympathetic, sensory and forebrain cholinergic neurons. NGF helps with nerve cell recovery after ischemic, surgical or chemical injuries, and promotes neurite outgrowth.(24C) The CA1 and CA3 regions of the hippocampal rat brain are both required for getting rid of fear, while the CA1 region is needed for context-dependent retrieval.(25C) Context-dependent retrieval refers to the encoding and retrieval of memories, often seen as someone being able to remember something in the same place that it was learned; such as taking an exam in the same classroom that information was learned.(26C) Alpha-Pinene reduces TNF-a,(12C) which shows many neuroprotective benefits.

Alpha-Pinene reduces interleukin-1β

A study gave neonate mice interleukin-1β. During adolescence, they showed signs of anxiety and deficits in long term spatial memory. That supports the view that inflammation problems that release IL-1β affecting the hippocampus during pregnancy produced behavioral problems in childhood that persists into adulthood. This inflammation is often from maternal infections during pregnancy, and premature births. Depending on the severity, children can have problems with motor skills, cognitive and behavioral problems, and even smaller brain volumes.(27C) Alpha-Pinene reduces interleukin-1β.(12C)

A-Pinene reduces NDMA2A (N-methyl- d-aspartate receptor subunits 2A)

and NDMA2B (N-methyl- d-aspartate receptor subunits 2B)

Activation of both NDMA2A and NDMA2B contribute to the phosphorylation of pERK1/2.30C ERK1/2 activity in some parts of the brain is needed for the processing of memories, and may be a target for treating memory impairments from neurological disorders.(31C) Overstimulation of these NDMA receptors during pregnancy is associated with compromised brain development.(32C) If these receptors are functioning abnormally low, it can result in cognitive problems, while overstimulation can cause excitotoxicity and lead to neurodegeneration.(33C) Alpha-Pinene reduces both of these receptors.(12C)

The role of a-pinene with these specific receptors will lower NDMA activity with the subunits 2A and 2B. This may be helpful with damage from overstimulating those receptors. Since a-pinene has other neuroprotective benefits, the lowering of these receptors in a normal brain might not produce problems, but that will require more targeted research. Given the intraperitoneal administration, the effects observed in the hippocampus likely reflect broader systemic changes in cell signals, potentially affecting other organs and tissues as well.

Alpha-Pinene reduces IL-6 (interleukin-6)

High levels of IL-6 in middle aged adults is associated with a lower volume of hippocampal gray matter.(28C) Elevated levels of IL-6 are also found in autism spectrum disorder, traumatic brain injury, ischemic stroke, tonic-clonic seizures, vascular dementia, and Alzheimer’s disease.(29C) Alpha-Pinene reduces IL-6.(12C)

Medication Interactions with Alpha-Pinene

Anticholinergics

Alpha-Pinene works on the opposing system that anticholinergics do, and could reduce the effectiveness of those medications. Anticholinergics are often used for nausea, overactive bladder. Acetylcholinesterase inhibitors have neuroprotective benefits, while anticholinergics that enter the CNS can accelerate neurodegeneration in Alzheimer’s disease. Long term use of medications that block CNS muscarinic cholinergic receptors (over 2 years of use), is associated with a 2.5 times higher density of amyloid plaque.(34C)

Anticholinergic medications, and what they are used for include:

-

Parkinson disease - Benztropine and trihexyphenidyl (35C)

-

Urinary incontinence or overactive bladder - Oxybutynin and tolterodine (35C)

-

Hyperhidrosis (Excessive sweating) - Oxybutynin (35C)

-

Allergies and sleep aid - Hydroxyzine, (36C) Diphenhydramine and other antihistamines (35C)

-

Nausea, IBS - Scopolamine,(35C) Dicyclomine, Hyoscyamine (36C)

-

Reduce salivary and tracheal secretions: Glycopyrrolate (35C)

-

Pupil dilation, cholinergic toxicity treatment: Atropine (35C)

-

Neuromuscular blockade for surgeries - Vecuronium and Succinylcholine (35C)

-

Ganglionic blocker in research settings - Mecamylamine (35C)

-

Depression - Amitriptyline, Doxepin (36C)

Dementia treating medications taken with a-pinene

There are medication interactions with Donepezil, as well as health problems that could cause problems if that medication is taken with certain conditions. This could possibly relate to similar interactions with a-pinene that people will need to keep in mind if they are trying to use that terpene.

Don’t use alpha-pinene along with a medication that increases acetylcholine like Donepezil. That would increase acetylcholine levels beyond the prescription alone. This may lead to toxic levels of acetylcholine. Here is what happens with excessive Ach levels happen with Donepezil toxicity:

Donepezil toxicity can result in nausea, vomiting, confusion, somnolence, diaphoresis and bradycardia.(37C) Excessive acetylcholine accumulation at the neuromuscular junctions and synapses can cause a cholinergic crisis that can include the following signs: ramps, increased salivation, lacrimation, muscular weakness, paralysis, muscular fasciculation, diarrhea, and blurry vision.(38C)

Can a-pinene worsen medications that affect the qt-interval?

Through the cholinergic effect on vagal tone at the sinoatrial and atrioventricular nodes; Donepezil can cause a slower heart rate (bradycardia), and interfere with potassium channel trafficking. Some cases of atrioventricular block and prolonged Qt interval have been studied from 2009 to 2017 with patients taking 5-10 mg of Donepezil, and an accidental overdose with 35mg that caused QTc = 502 ms. (39C)

Taking a-pinene along with medications that increase the Qt interval could worsen the problem due to the parasympathetic response to the extra acetylcholine from a-pinene. The heart rate could become too slow, or even go into a lethal rhythm like torsades de pointes.

Medications that can increase the Qt interval include:

Antipsychotics - Haloperidol, ziprasidone, quetiapine, thioridazine, olanzapine, risperidone, droperidol (40C)

Antiarrhythmics - Amiodarone, sotalol, dofetilide, procainamide, quinidine, flecainide (40C)

Antibiotics - Macrolides, fluoroquinolones (40C)

Antidepressants - Amitriptyline, imipramine, citalopram, amitriptyline (40C)

Others - Methadone, sumatriptan, ondansetron, cisapride (40C)

Medications that lower the heart rate can result in a dangerously low rate if used with Donepezil, such as beta-blockers - carvedilol, metoprolol, atenolol, and propranolol.(41C) There is a possibility that this effect could also happen with alpha-pinene.

Beta-Pinene

-/- Beta-Pinene

+/- Beta-Pinene

(+/-)- Beta-Pinene

Receptor interaction

Beta Pinene is a 5-HT3 receptor antagonist (40D)

(+/-)- Beta Pinene is found in: Eucalyptus Oil, Mandarin oil, Juniper Berry Oil, Cannabis (46C)

+/- Beta Pinene is found in Salvia officinalis (Sage), Pinus sylvestris (Scots Pine) (47C)

-/- Beta Pinene found in Camellia sinensis (tea), and Magnolia officinalis (48C)

Beta-Pinene for irritable bowel syndrome, nausea and vomiting

Beta-Pinene is a 5-HT3 receptor antagonist.(40D) 5HT3 antagonists can be used to treat certain types of irritable bowel syndrome and relieve nausea and vomiting. It is a type of antiemetic. 5HT3 is also called 5-hydroxytryptamine 3 receptor and type 3 serotonin receptor. (41D)

Clarifying online misinformation about beta-pinene

There are not many useful studies that are specifically about beta pinene. Some sources indicate that beta pinene has similar benefits as alpha pinene for antimicrobial and anticancer.(49C) When checking the sources they cited showed that alpha pinene was used in the study for anticancer. Here is the exact wording of the conclusion from that source: "In a dose-related fashion, alpha-pinene inhibits the nuclear translocation of NF-kappa B induced by LPS in THP-1 cells, and this effect is partly due to the upregulation of I kappa B alpha expression." (50C)

The original source for the antibacterial benefits used an essential oil extracted from the gum of the pistachio tree grown in Turkey, that had the composition of: alpha-Pinene (75.6%), beta-pinene (9.5%), trans-verbenol (3.0%), camphene (1.4%), trans-pinocarveol (about 1.20%), and limonene (1.0%). (51C) So, it really cannot be said that beta-pinene has anti-bacterial properties based on that information.

Even though alpha pinene and beta pinene are structurally similar, they may not act the same therapeutic way as each other. More specific research using isolated beta-pinene would be needed to make those claims. The antibacterial benefits could be from an entourage effect of some or all the terpenes, or may just be alpha pinene. The anticancer benefits were clearly from alpha pinene, as that is what was used in the study.

Linalool

-/- Linalool

+/- Linalool

(+/-)- Linalool

Receptor interaction

Linalool inhibits the release of Acetylcholine (ACh) at the neuromuscular junction. A local anesthetic reaction occurs due to the reduction of the channel open time. (55C) Linalool is also a NMDA receptor antagonist. (12F)

-/- linalool is found in lavender oil, Camellia sinensis (a type of tea), and Solanum tuberosum (potato) (56C)

+/- linalool is found in coriander oil, Agastache rugosa (korean mint), and Eremothecium ashbyi which is a pathogen that is found on cotton and citrus; that pathogen is used is the industrial production of riboflavin. (57C,58C )

(+/-)- linalool is found in Cinnamon Leaf Oil, Cinnamon Bark Oil, Clary Sage Oil, Peumus boldus leaf, Cannabis, Paeonia lactiflora root (Peony), and Moringa oleifera leaf oil. (59C)

Is Linalool is antibacterial?

A study about the antibacterial effects of coriander essential oil and its major constituent, linalool (content of 70.11%) was found to have a synergistic effect by increasing the effectiveness of antibiotics against MRSA, gram negative, and gram positive bacteria.(60C)

Coriander oil is composed of borneol, cineole, coriandrol, cymene, dipentene, geraniol, linalool, phellandrene, terpineol, and terpinolene. All the terpenes will vary depending on which country the coriander was grown in, and there are 21 different terpenes in coriander seeds, but several are not present in different regions. The level of +/- linalool can vary from 37.7 - 78.45% depending on the country grown in. (61C)

Linalool as an anti-inflammatory

In a study using lipopolysaccharides (LPS) to induce inflammation in BV2 microglial cells, linalool was found to inhibit the production of inflammatory mediators such as TNF-α, IL-1β, NO, and PGE2, and also inhibited NF-κB activation. Additionally, linalool induced the nuclear translocation of Nrf2 and the expression of HO-1, suggesting that its anti-inflammatory effects are mediated through the activation of the Nrf2/HO-1 pathway.(62C)

Neuroprotection

It has been proposed that linalool could be a benefit for Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease due the anti-inflammatory effect in the BV2 microglial cells,(63C) but linalool will inhibit the release of acetylcholine. This study did not mention which enantiomer of linalool was in the plant they were researching, but it was from Aeolanthus suaveolens, which is a Brazilian Amazon plant that is used as an anticonvulsant.(64C) In Alzheimer’s disease, ACh needs to be increased, and an acetylcholinesterase inhibitor is often prescribed to improve cognition and behavior.(65C) People afflicted with Parkinson’s are often prescribed anticholinergics along with a dopamine-increasing medication like Levodopa.(66C) Linalool could be causing more side effects with prescriptions, and be counterproductive with these neurodegenerative diseases due to the lowering of ACh.

Anti-leishmaniasis

Linalool and Eugenol both decrease the proliferation and viability of Leishmania (L.) infantum chagasi (Leishmania amazonensis) and Trypanosoma cruzi at low doses. Both terpenes increased the activity of L. infantum chagasi protein kinases PKA and PKC. Linalool also decreased the oxygen consumption of L. infantum. The lethal dose against L. infantum LD50 for eugenol was 220μg/ml, and that for linalool was 550μg/ml. (67C)

Myrcene

Receptor interaction

TRPV1 agonist, (68C) mu-opioid and alpha 2-adrenoreceptor modulation (69C)

Myrcene Relieves Pain

A 1990 study showed that myrcene released endogenous opiates that relieved pain, and that effect was reversed with Narcan (Naloxone). That effect involved alpha 2-adrenoceptor and mu-opiod receptors.(69C) A 2003 study further explained that mu-opioid receptors and alpha 2A-adrenergic receptors can physically interact and modulate each other’s signaling pathways.(70C) It is still not known if myrcene is an agonist of the alpha 2-adrenoceptor, or if myrcene indirectly modulates that receptor through interacting with a different receptor.

Other ligands, such as adrenaline (epinephrine), will interact with the alpha 2A-adrenergic receptors.(71C) Using epinephrine along with bupivacaine and fentanyl via epidural was found to decrease pain and the needs for opiates after surgery for pain relief.(72C) Epinephrine and myrcene could be helping with pain relief in similar ways from the release of endogenous opiates, but the side effects would be different between the two.

Myrcene inhibits cytochrome p450 CYP2B1

Myrcene inhibits the liver enzyme, cytochrome p450 CYP2B1. This can have a protective benefit against pro mutagenic chemical toxins. Myrcene, along with seven other terpenes, will inhibit the cytochrome p450 CYP2B1 enzyme.(73C) Inhibiting this enzyme can affect the absorption of other medications.

Myrcene blocks prostaglandin E2 (PGE2)

Myrcene can reduce pain and inflammation that is caused by prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), and does not create tolerance problems like morphine does.(74C) PGE2 is created when arachidonic acid is converted to prostaglandin H2 (PGH2) by PGE synthases (cPGES, mPGES-1, mPGES-2). Targeting the PGE synthase mPGES-1 to disrupt PGE2 formation may help alleviate inflammation, pain, fever, anorexia, atherosclerosis, stroke, and tumorigenesis.(75C) Myrcene may be able to help with these conditions by blocking PGE2 from interacting with its receptors. Myrcene does not block the mPGES-1 pathway, but indirectly reduces the effects of PGE2.

Does Myrcene cause cancer?

Studies in mice and rats showed that they get liver cancer when exposed to myrcene.(76C) Let's look at the extremely high doses in the study, and compare that to what some cannabis users get.

3-Month Study in Mice:

Doses: 0.25 to 4 g/kg body weight, administered 5 days a week for 14 weeks.

Results: High mortality and significant health issues at 1 g/kg and above.(76C)

2-Year Study in Rats:

Doses: 0.25 to 1 g/kg body weight, administered 5 days a week for 105 weeks.

Results: Significant renal toxicity and increased incidence of renal and liver neoplasms.(76C)

2-Year Study in Mice:

Doses: 0.25 to 1 g/kg body weight, administered 5 days a week for 104-105 weeks.

Results: Increased incidence of liver neoplasms and decreased survival rates.(76C)

Human doses with myrcene-rich cannabis products

Dried cannabis typically has a low terpene content of 1-3%, since most of the terpenes are lost while the plant is drying. Freshly harvested marijuana can be extracted by CO2 to retain the most terpenes. The highest amount of myrcene I have seen on a lab test for a CO2 extract is 6%. Most of them are less than 2%.

Let’s compare how the mouse study compares to doses a human would encounter with an edible with 1000 mg of cannabis oil at 6% myrcene for a 150 lbs person. (about 68 kg)

1000mg of cannabis oil is an extremely high amount, while edibles are often lower at 25-50mg per dose. If someone ate the 1000mg dose of cannabis oil at 6% myrcene, that would be 60mg of myrcene. This comes out to about 0.88mg per kg. Compared to the lowest dose in the mice study at 250mg per kg (0.25g/kg). Even at that extreme dose of cannabis oil, that is still a very low dose of myrcene compared to the mouse study. The mouse study is 284 times higher than an extreme dose for a human.

If a 150 lbs person smoked 1 gram of marijuana containing 2% myrcene, they would consume approximately 20 mg of myrcene, which equates to about 0.29 mg per kg of body weight. Most people don’t smoke 1 gram or more in a single session, making this an extreme case. Even at such a high intake, the myrcene levels are a fraction of the doses used in animal studies that showed toxic or carcinogenic effects. For example, the doses in the 3-month mouse study were as high as 1 g/kg, which is 862 times greater than the estimated dose from smoking. Similarly, in the 2-year studies, the doses were 284 times higher than what a human would ingest even with a substantial dietary intake of myrcene at 0.88 mg per kg. These comparisons highlight the significant difference between experimental doses in animal studies and realistic human exposure through cannabis use.

It looks like it is unlikely for a human to get liver cancer from myrcene with cannabis use. They would be more likely to get problems with using a large amount of isolated myrcene in a topical, and with long term use.

Myrcene as a sedative, muscle relaxer, and anti-anxiety

Myrcene has sedative and muscle relaxant properties. There may be some anxiety relief at lower doses, but may cause anxiety with larger doses.(77C) There are two different studies from 1991 and 2002 that explored different routes of administration, and different neurobehavioral effects.

The 1991 study showed no change in anxiety, or behavior change at 1g of myrcene per kilogram by mouth.(78C) The 2002 study showed sedative as well as motor relaxant effects at 100-200 mg/kg from an intraperitoneal injection. The 200 mg/kg dose of myrcene had a slight anxiety inducing effect.(77C) The difference in administration and the doses being higher in the 1991 study could be two possibilities there were no anti-anxiety benefits.

Doses for rats are not scalable to humans

Those doses mentioned in the studies are for rodents, and human doses would be very different. Human doses are often calculated from rodent doses using allometric scaling, which accounts for differences in body surface area and metabolism between species. This involves multiplying the rodent dose by a conversion factor based on the animal's weight and body surface area, typically resulting in a lower dose for humans due to their slower metabolic rates.(79C)

Delta-3 Carene

Receptor interaction

Carene is an acetylcholinesterase inhibitor (52C)

Carene is a colorless liquid with a sweet, turpentine-like odor. It is found in cannabis, Artemisia thuscula, and Cymbopogon martinii. (53C)

Carene goes by 64 different names, including: (+)-3-carene, Delta-3-Carene, and alpha-Carene. (53C)

Toxicity from occupational frequent contact with carene is allergic contact dermatitis and asthma. Poisoning from it can result in encephalopathy, that is because it is a solvent. (53C)

Delta-3 Carene for Osteoporosis Treatment

In an mouse in-vitro study with osteoblastic MC3T3-E1 subclone 4 cells, 3-carene stimulated alkaline phosphatase on the ninth day. The fifteenth day, 3-carene promoted the induction of calcium in a dose dependent manner. This early research indicates 3-carene might be useful for treating osteoporosis, but that needs further research. (54C)

Beta-caryophyllene

-/- b-caryophyllene

+/- b-caryophyllene

Isocaryophyllene

Receptor interaction

CB2 agonist (72A) and acetylcholinesterase inhibitor with an IC(50)=436.0±29.9 (37E)

(-)-beta-caryophyllene is the most common isomer of the different versions of beta-caryophyllene. It is found in clove oil and tea leaves (camellia sinensis). This terpene has the odor midway between cloves and turpentine. This isomer is the one associated with cannabis, and acts as a CB2 receptor agonist.(80C,81C)

(+)-beta-caryophyllene is the enantiomer of (-)-beta-caryophyllene. It is found in Morithamnus crassus (in the Asteraceae family), and Solanum tuberosum (potatoes). (82C)

Isocaryophyllene is another type of caryophyllene that is found in Tetradenia riparia, and Perilla frutescens that are both in the mint family Lamiaceae. (83C)

Is Caryophyllene an anti-inflammatory via PGE-1 comparable phenylbutazone?

There has been a mention in a journal that β-caryophyllene is an anti-inflammatory via PGE-1 (Prostaglandin E1) comparable phenylbutazone.(84C) The 1988 study that was referenced in that journal referred to the oleoresin from Brazilian Copaifera species that had an anti-inflammatory activity comparable to phenylbutazone.(85C) There are three main terpenes in that resin, which are β-caryophyllene, trans-α-bergamotene, and β-bisabolene.(86C) It is difficult to say if β-caryophyllene is solely the anti-inflammatory affecting PGE-1, or if that is from a combination of 2 or 3 terpenes found in that oleoresin.

Β-caryophyllene is an anti-inflammatory

β-Caryophyllene is an anti-inflammatory from activating the CB2 receptor. This acts on the MAPK pathway, through inhibiting the Erk1/2 and JNK1/2 kinases. β-Caryophyllene also reduces the proinflammatory cytokines IL-1β, IL-6, and TNFα. (81C)

Beta-Caryophyllene against MCF-7, DLD-1 and L-929 cancer cell lines

Beta-Caryophyllene enhances the anticancer effects of alpha-humulene, isocaryophyllene and paclitaxel against MCF-7, DLD-1 and L-929 cancer cell lines.(87C)

Terpenes tested against MCF-7 Breast Cancer Cell Line

Alpha-humulene inhibited MCF-7 by 50% (87C)

Isocaryophyllene inhibited MCF-7 by 69% (87C)

Beta-Caryophyllene with a-humulene inhibited MCF-7 by 75% (87C)

Beta-Caryophyllene with Isocaryophyllene inhibited MCF-7 by 90% (87C)

Beta-Caryophyllene enhances paclitaxel

Beta-Caryophyllene helped to facilitate the passage of paclitaxel through the membrane, increasing anticancer activity of paclitaxel.(87C) Paclitaxel is a chemotherapeutic drug that is used in AIDS-related Kaposi sarcoma, Breast cancer, Non-small cell lung cancer, and Ovarian cancer.(88C)

Can Caryophyllene help reduce addiction to cocaine?

CB2 receptors in the brain modulate the rewarding effect and locomotor-stimulating effects of cocaine. This is probably from a dopamine-dependent mechanism. A study showed how a CB2 agonist, JWH133, reduced cocaine self administration and cocaine enhanced locomotion. This may reduce the extracellular dopamine in the nucleus accumbens. The CB2 inverse agonist, AM630, blocked the effect of JWH133, which increased cocaine self-administration and enhanced reward. The CB2 inverse agonist increases extracellular dopamine and loco motion.(89C) CB2 agonists could use further research on how they can help with other dopamine-rewarding addictions such as alcohol, opioids, gambling, and more. Combining caryophyllene with other CB2 agonists, like CBD, may help even more.

Can β-Caryophyllene help with itching?

There has been a proposal that β-Caryophyllene may help with itching (pruritus) through the CB2 receptor.84C Contact dermatitis could be improved with cannabinoid receptor agonists, and the allergic inflammation could be worsened with cannabinoid receptor antagonists.(90C) A clinical study revealed that a CB2 agonist, JWH-133, reversed inflammation and scratching.(91C) CB1 has also been found to help with itching through neuronal mechanisms, and does not influence histamine (H1 antagonism) or mast cell deficiencies.(92C) Cannabinoids could be helpful with several types of conditions that cause itching, including atopic dermatitis, psoriasis, asteatotic eczema, prurigo nodularis, and allergic contact dermatitis, uremic pruritus and cholestatic pruritus.(93C) It does appear that caryophyllene could help with itching through CB2 agonism. Adding in CB1 agonists could further help reduce itching.

Is Caryophyllene an anti-malarial?

It has been proposed that caryophyllene could be helpful against malaria.(84C) The original study was using essential oil from the leaves and stems of Tetradenia riparia, which had 35 components including alpha-terpineol (22.6%), fenchone (13.6%), beta-fenchyl alcohol (10.7%), beta-caryophyllene (7.9%), and perillyl alcohol (6.0%).(94C) Let’s take a look at each terpene separately to see if caryophyllene is helpful against malaria. Alpha-terpineol can help prevent asthma by regulating arachidonic acid metabolism. In a study, α-terpineol reduced the leukocyte count and inflammatory cytokines in the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid of the asthmatic mice.(95C) A-terpineol can penetrate the blood brain barrier to reduce glioblastoma growth, migration, invasion, angiogenesis and temozolomide resistance. This terpene targets KDELC2 to downregulate Notch and PI3k/ mTOR/MAPK signaling pathway.(96C)

Fenchone has the properties of anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, diuretic, wound-healing, antidiarrheal, antifungal, antinociceptive, and bronchodilator.(97C) Beta-fenchyl alcohol does not have much medical research or known medical properties. Perillyl alcohol has anti-cancer properties that was shown to regress pancreatic, mammary, and liver tumors. It may be helpful with colon, skin, and lung c, neuroblastoma, prostate, and colon cancer.(98C) Beta-caryophyllene is a CB2 agonist.(81C) This may help with the immune system regulation, and possibly help with malaria. With the other terpenes found in Tetradenia riparia, it is hard to say that caryophyllene by itself would be anti-malarial, or if the combination of the terpenes are what is needed to treat malaria.

Β-caryophyllene as a gastric cytoprotective

Β-caryophyllene can reduce gastric mucosal injuries from necrotizing products like ethanol and 0.6 N HCL. This terpene was fed to rats to discover this property. It did not prevent gastric injuries from other methods like water immersion stress- and indomethacin-induced gastric lesions. It also did not change the secretion of gastric acid and pepsin,(99C) this indicates that caryophyllene’s protective effects are not due to changes in gastric secretion.

Beta-Caryophyllene Oxide

Receptor interaction

Mild effect as an acetylcholinesterase inhibitor at IC(50)=320.16 ± 13.47 (37E)

Caryophyllene Oxide is found in Cannabis, Annona squamosa, Camellia sinensis, and Artemisia thuscula.(1D)

Caryophyllene Oxide isolated from the bark of Annona squamosa showed properties of being an anti-inflammatory and produced central and peripheral analgesia.(2D) The mechanism behind those properties were not explained in the abstract part of the journal that is posted online.

Anti-Cancer

Caryophyllene Oxide showed in-vitro cytotoxic effects against the following human cancer cell lines:

Leukemia cancer cell line HepG2 IC50 = 3.95 ± 0.23 (3D)

Lung cancer cell line AGS IC50 = 12.6 ± 0.86 (3D)

Cervical adenocarcinoma cell line HeLa IC50 = 13.55 ± 0.45 (3D)

Gastric cancer cell line SNU-1 IC50 = 16.79 ± 1.2 (3D)

Stomach cancer cell line SNU-16 IC50 = 27.39 ± 1.4 (3D)

Ovarian cancer cell line A-2780 IC50 = 8.94 x 10(-3)mg/ml (4D)

Anti-Fungal

Caryophyllene oxide demonstrated antifungal properties for treating onychomycosis that were comparable to those of ciclopiroxolamine and sulconazole. (5D)

Humulene

Receptor interaction

Humulene interacts with CB1 and Adenosine A2A receptors.(6D) It is still not known if humulene is an agonist or modulator of those receptors. Humulene is an acetylcholinesterase inhibitor with an IC(50)=785.3 ± 66.0 (37E)

Humulene is also known as alpha-caryophyllene.(7D)

Humulene (and their content percentages) is found in Aframomum melegueta (alligator pepper) 60.9%, Leptospermum sp. leaves (Mt Maroon A. R. Bean 6665) 44-51%, Humulus lupulus (Chinook variety) 31.50 – 34.62%, Camponotus japonicus (insect) 35.80%, and Zingiber nimmonii 19.60%. (6D) It is also in some cannabis strains.

Humulene for allergic airway inflammation treatment

A mouse study using aerosolized humulene (1 mg/ml) in an experimental allergic model showed decreased levels of IL-5, CCL11, and LTB4 in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF). Humulene also reduced the activation of NF-κB and AP-1 transcription factors. This suggests that humulene's anti-inflammatory effects could be beneficial as a preventive or therapeutic treatment for allergic airway inflammation.(10D)

Can Humulene lower blood sugar in diabetes, and help with weight loss?

There is limited research on isolated humulene and its effects on blood sugar. It is known that a-humulene can cause weight loss (8D) that can possibly be linked to it acting as a stimulant and possibly lowering blood sugar, but that needs more targeted research. Clove essential oil was found to lower blood sugar, and is made of over 50% eugenol, while eugenyl acetate, β-caryophyllene, and α-humulene make up most of the rest of clove oil. There are many trace terpenes in about 10% of the clove oil that include cadinene, caryophyllene oxide, chavicol, diethyl phthalate, 4-(2-propenyl)-phenol, α-cubebene, and α-copaene, and more.(9D)

The many benefits of humulene

Humulene has anti-inflammatory, anticancer, antibacterial, antiparasitic, antifungal, and pain relieving effects. It is effective against many different cancers including colon, ovarian, hepatocellular, lung, breast, cervical, and kidney. (6D)

Humulene against liver cancer

α-Humulene exhibits anticancer effects against hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) by inducing mitochondrial apoptosis, as evidenced by caspase-3 activation and PARP cleavage. HCC cells typically resist apoptosis due to abnormal Akt signaling. Humulene inhibits Akt signaling, leading to decreased GSK-3 activity and reduced phosphorylation of BAD (Bcl-2-associated agonist of cell death), thereby promoting apoptosis.(8D)

Cytotoxicity of Humulene in In Vitro Cancer Models (IC50 Values)

Human colon cancer (HT-29): IC50 = 5.2 × 10-5 mol/L (6D)

Human hepatocellular carcinoma (J5): IC50 = 1.8 × 10-4 mol/L (6D)

Human pulmonary adenocarcinoma (A549): IC50 = 1.3 × 10-4 mol/L (6D)

Human colon adenocarcinoma (HCT-116): IC50 = 3.1 × 10-4 mol/L (6D)

Human breast cancer (MCF-7): IC50 = 4.2 × 10-4 mol/L (6D)

Murine macrophages (RAW264.7): IC50 = 1.9 × 10-4 mol/L (6D)

Terpineol

-/- alpha-terpineol

+/- alpha-terpineol

4-terpineol (+/-)-

gamma-terpineol

Receptor interaction

Anticholinergic (11D) (inhibits muscarinic acetylcholine receptors)

+/- alpha-terpineol is found in cannabis, coriander oil, Peumus boldus leaf, Camellia sinensis (tea), Callistemon citrinus.(12D)

-/- alpha-terpineol is found in Guarea macrophylla, Pinus densiflora.(13D)

4-terpineol, (+/-)- is found in lavender oil, juniper berry oil, Peumus boldus leaf, Anthriscus nitida, Tetradenia riparia,14D and turmeric seeds.(15D)

Gamma-terpineol is found in Ambrosiozyma monospora, and Plumeria rubra.(16D)

Gamma-terpineol against liver cancer

Gamma-terpineol was found to have anti-cancer effects and induce apoptosis with liver cancer.(17D) Gamma-terpineol has limited research available.

Health benefits about alpha-terpineol is often confused with 4-terpineol

Alpha-terpineol is often confused with 4-terpineol, especially with health benefit claims. Specific research needs to be done on a-terpineol to verify if that isomer has the same effects as 4-terpineol.

Alpha-Terpineol research - anticancer, anti-inflammatory, antioxidant

a-Terpineol significantly suppressed glioblastoma growth migration, invasion, angiogenesis, proliferation, and temozolomide (TMZ) resistance. This terpene targeted KDELC2 to downregulate Notch and PI3k/mTOR/MAPK signaling pathway. a-Terpineol can penetrate the blood brain barrier to inhibit the proliferation of glioblastoma, adding the benefit of having a reduced cytotoxicity to vital organs.(18D)

a-Terpineol has anti-inflammatory effects, acts as an expectorant, and may help prevent asthma from regulating a disorder in arachidonic acid metabolism. In a study, a-Terpineol alleviated asthma in mice by lowering arachidonic acid level, downregulates the expression of 5-LOX and reduced the accumulation of CysLTs. This reduced airway inflammation, mucus hypersecretion and Th1/Th2 immune imbalance.(19D)

a-Terpineol is a strong antioxidant comparable to commercial antioxidants, and has strong anti-cancer effects in breast cancer and chronic myeloid leukemia.(20D)

Can a-terpineol cause fatty liver?

A study with mice indicated that it might induce fatty liver through the AMPK/mTOR/SREBP-1 pathway.(21D) Further research is necessary to understand the implications for human use, particularly regarding dosage and long-term effects. Users should exercise caution and consult healthcare professionals before extensive use. There was no mention of doses used in the mouse study abstract available online, like the obscenely large doses of myrcene used in the liver cancer study.

α-Terpineol as an anticholinergic and anti-diarrhea

α-Terpineol has demonstrated anticholinergic properties and significant antidiarrheal effects in a study involving mice. The study showed that α-terpineol reduced total stool amount and diarrhea through mechanisms involving the blocking of PGE2 and GM1 receptors, and interaction with cholera toxin. Specifically, α-terpineol reduced fluid formation and chloride ion loss. The tested doses (6.25, 12.5, 25, and 50 mg/kg) showed reductions in total stool amount by 55%, 48%, 44%, and 24%, respectively, and reductions in diarrhea by 47%, 66%, 56%, and 10%, respectively.(11D)

The study did not provide detailed information on whether the specific doses correlated directly with the percentage reductions in diarrhea. If we assume that the doses correspond to the reported percentages, the 50 mg/kg dose appears to have the lowest percentage reduction in diarrhea at 10%. This suggests that the highest dose tested might be less effective in reducing diarrhea compared to lower doses, although the exact correlation remains unclear from the abstract available online.

4-Terpineol medicinal benefits

4-Terpineol is known to be an antibacterial agent, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory agent, antiparasitic agent, antineoplastic agent, and an apoptosis inducer.(14D)

4-Terpineol is anti-bacterial

4-Terpineol, also known as terpinen-4-ol, has antibacterial properties against periodontal bacteria. These are the bacteria tested in a study, along with concentrations to inhibit the bacterial growth, and to act as a bactericidal: (22D)

Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) (22D):

E. faecalis: 0.25%

F. nucleatum: 0.25%

P. gingivalis: 0.05%

P. intermedia: 0.1%

Minimum Bactericidal Concentration (MBC)(22D):

E. faecalis: 1.0%

P. gingivalis: 0.2%

P. intermedia: 0.2%

F. nucleatum: 0.5%

Anti-cancer effects of 4-Terpineol

4-Terpineol was found to induce ferroptosis in glioma cancer cells.(15D) Ferroptosis is a type of cell death from iron-dependent lipid peroxide accumulation. This type of cell death is from cytological changes, including cell volume shrinkage and increased mitochondrial membrane density. (23D) The anti-cancer effects from 4-terpineol is from the induction of JUN/GPX4-dependent ferroptosis and inhibiting cell proliferation.(15D)

Anti-cancer effects of different types of terpineol

IC50 concentrations against lung adenocarcinoma cells (A549)(24D):

Terpinen-4-ol: 0.06%

Sabinene hydrate: 0.06%

alpha-terpinene: 0.06%

gamma-terpinene: 0.13%

IC50 concentrations against lung large-cell carcinoma cells (LNM35) (24D):

Terpinen-4-ol: 0.02%

Sabinene hydrate: 0.05%

alpha-terpinene: 0.04%

gamma-terpinene: 0.08%

4-terpineol was found to inhibit the growth of colorectal, pancreatic, prostate and gastric cancer cells.(25D)

Ocimene

Beta-Ocimene (3E)-

Beta-Ocimene (3Z)-

No receptors identified that ocimene interacts with.

Beta-Ocimene, (3E)- is found in cannabis, Camellia sinensis (tea), and Salvia rosmarinus (rosemary). (26D)

Beta-Ocimene, (3Z)- is also found in cannabis, Camellia sinensis (tea), and Pilocarpus microphyllus (Arruda and Maranham Jaborandi).(27D,28D)

Many health claims about ocimene are inaccurate

It appears ocimene needs research on its properties. There are minimal proven health benefits of ocimene. Many online claims are not accurate.

Some popular cannabis websites claim that ocimene has notable health benefits based on studies involving essential oils. These claims often come from studies where ocimene is one of several active compounds, making it difficult to attribute the effects to ocimene alone.

Ocimene has antileishmaniasis properties

Ocimene has cytotoxic effects against leishmaniasis, and reduces IL-10 and IL-6. It also increases lysosomal activity and TNF-α, NO, and ROS. (59F)

Ocimene against cancer

Studies online have not shown the specific anticancer effects of ocimene, or if it was anticancer by itself. There is one study mentioning that ocimene combined with the flavonoid kaempferol potentiates the anticancer effects against Taxol-resistant MCF-7 breast cancer. (58F)

Kaempferol is a natural flavonoid which has been isolated from Delphinium, Witch-hazel, grapefruit, cannabis, and more. (60F) Kaempferol has anticarcinogenic, anti-inflammatory, antibacterial, antifungal, and antiprotozoal activities. (61F)

Claim debunking 1 - treatment for diabetes

The claim made about ocimene being a possible treatment of diabetes type 2 was based on black pepper essential oil with the terpene breakdown of α -Pinene, β -pinene, cis-ocimene, myrcene, allo-ocimene, and 1,8-cineole. (30D) Only the abstract is available online, and there were no percentages on the abstract.

1,8-Cineole has been shown to lower blood sugar levels, making it more likely that the anti-diabetic effects observed in the study were due to 1,8-cineole rather than ocimene. Here is the word for word part of the study: “1,8 cineole ameliorated diabetic nephropathy via the reduction of TGF-1β following to decrease the formation of different glycation products, oxidative stress, and inflammatory process with the induction of the activity of glyoxalase-I and the advantageous effect on glucose and lipid metabolism as well as insulin sensitivity in type 2 diabetic rats.” (31D)

Claim debunking 2 - aphid repellent

Another claim made about ocimene is that it has aphid-repelling properties.(38E) This claim is based on a study where tomato plants overexpressed ocimene in response to an aphid attack, resulting in significantly lower numbers of aphids, fewer newborn nymphs, and reduced aphid weight. Ocimene appears to have more of a role in plant communication rather than directly acting as an aphid repellent. The study indicated that tomato plants exposed to ocimene released other volatile organic compounds like methyl salicylate and cis-3-hexen-1-ol, which are known to impair aphid development and reproduction and attract aphid parasitoids. While ocimene may not directly repel aphids, it plays a crucial role in eliciting plant defenses that create an environment less favorable for aphids and more attractive to their natural enemies.(32D)

Eucalyptol (1,8-Cineole)

Receptor interaction

Eucalyptol is a TRPM8 and TRPV3 agonist, and a TRPA1 antagonist.(38A,33D)

Eucalyptol is a natural product found in eucalyptus oil, Curcuma xanthorrhiza, Baeckea frutescens, Paeonia lactiflora root, Rosemary, and many others.(34D,36D)

Eucalyptol has a camphor-like odor, and a spicy cooling taste. It is often used in mouthwash and in cough suppressants. Eucalyptol can control airway mucus hypersecretion and asthma from inhibiting anti-inflammatory cytokines. It can also treat nonpurulent rhinosinusitis, reduce inflammation and pain when applied topically, and can kill leukemia cells in vitro.(34D)

Eucalyptol can help with diabetes and diabetic nephropathy

Eucalyptol can help diabetic nephropathy through reducing TGF-1β, which then decreases the formation of different glycation products, oxidative stress, and inflammatory processes. It also induces glyoxalase-I, and enhances glucose metabolism, lipid metabolism, and insulin sensitivity.(35D)

Asthma and COPD

Eucalyptol can help with inflammatory airway diseases, such as asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). It acts as a mucolytic by breaking apart and thinning mucus, and it reduces spasms by controlling the inflammatory process that causes infection and mucus hypersecretion. (37D)

Eucalyptol’s anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects

Eucalyptol can help with respiratory disease, pancreatitis, colon damage, and cardiovascular and neurodegenerative diseases through its anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects. This terpene reduced the action of NF-κB, TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 and the extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) pathway.(38D)

Could eucalyptol have side effects?

Since eucalyptol can lower blood sugar,(35D) then it is possible that people that are prone to hypoglycemia could experience a low blood sugar episode with eucalyptol. This can depend on individual sensitivity, and dose.

Low blood sugar symptoms include feeling shaky or jittery, hungry, tired, dizzy, lightheaded, confused, irritable, headache, heart beating too fast or not steadily, or having a hard time speaking clearly.(39D)

Alpha-Phellandrene

-/- a-phellandrene

+/- a-phellandrene

(+/-)- a-phellandrene

Receptor interaction

5-HT3 receptor antagonist (40D)

-/- a-phellandrene is found in eucalyptus oil, Camellia sinensis, Magnolia officinalis.(42D)

+/- a-phellandrene is found in Smallanthus fruticosus, Thymus camphoratus.(43D )

(+/-)- a-phellandrene is found in cannabis, Artemisia thuscula, Espeletia weddellii.(44D) Artemisia thuscula is commonly used as a diuretic in the Canary islands.(45D)

α-Phellandrene against leukemia

Alpha-Phellandrene induced apoptosis in vitro with mouse leukemia WEHI-3 cells. α-Phellandrene induced G0/G1 arrest and sub-G1 phase, and triggered the release of cytochrome c, AIF, and Endo G from mitochondria.(46D)

The antifungal effects of α-Phellandrene alone and with Fluconazole and Amphotericin B

α-Phellandrene alone has strong antifungal activity against C. albicans, with a zone of inhibition of 24 ± 0.5 mm for MTCC277 and 22 ± 0.5 mm for ATCC90028.(47D)

Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) of α-Phellandrene ranges from 0.0312 to 0.0156 mg/ml against C. albicans strains.(47D)

Combination Treatments

Alpha-Phellandrene with Fluconazole: log10 reduction of 2.56 ± 0.33 (ATCC90028) and 2.53 ± 0.33 (MTCC277) after 16 hours.(47D)

Alpha-Phellandrene with Amphotericin B: log10 reduction of 2.42 ± 0.28 (ATCC90028) and 2.00 ± 0.21 (MTCC277) after 16 hours.(47D)

The study suggests significant synergistic effects when α-Phellandrene is combined with conventional antifungal drugs, leading to increased antifungal activity and potential for use in new antifungal treatments.

Alpha-phellandrene for irritable bowel syndrome, nausea and vomiting

Alpha-phellandrene is a 5-HT3 receptor antagonist.(40D) 5HT3 antagonists can be used to treat certain types of irritable bowel syndrome and relieve nausea and vomiting. It is a type of antiemetic. 5HT3 is also called 5-hydroxytryptamine 3 receptor antagonist and type 3 serotonin receptor antagonist.(41D)

Alpha-phellandrene against liver cancer

Alpha-phellandrene was shown to induce necrosis to liver cancer cells through the depletion of ATP.(48D) It can also induce autophagy in the liver cancer cells from regulating mTOR and LC-3II expression, p53 signaling, and NF-κB activation.(49D)

Alpha-phellandrene is an anti-inflammatory

Alpha-phellandrene is an anti-inflammatory from inhibiting the production of TNF-α and IL-6; as well as through neutrophil migration modulation and mast cell stabilization.(50D)

Alpha-phellandrene for depression?

It has been mentioned that a-phellandrene could help with depression.(51D) The mechanism of this is not mentioned, but could have to do with modulating the intestinal contractions providing a serotonin feedback to the brain, or the alleviation of the symptoms may be another reason for its anti-depressant qualities.

Alpha-Bisabolol

-/- a-bisabolol

+/- a-bisabolol

(+/-)- a-bisabolol

Receptor interaction

(-)-α-bisabolol is a TRPA1 and TRPV1 antagonist. COX-2 modulator (52D,53D,62D)

Alpha-bisabolol is found in cannabis, but it is not known which isomer is.

(-)- alpha-bisabolol (Levomenol) is found in Picea jezoensis, Abies nephrolepis, Chamomile, Aesculus chinensis, and other plants.(54D)

(+)- alpha-bisabolol is found in Lasiolaena morii and Microbiota decussata.(55D)

(+/-)- alpha-bisabolol is found in Artemisia princeps and Peperomia galioides.(56D)

The many benefits of a-bisabolol

Alpha-bisabolol has anticancer, antinociceptive, neuroprotective, cardioprotective, and antimicrobial effects.(57D)

Alpha-bisabolol for skin ulcer healing

A study compared the healing effects of ozonated oil containing 25% α-bisabolol to a standard epithelialization cream with vitamin A, vitamin E, talc, and zinc oxide on chronic venous leg ulcers. The results showed significantly better wound healing with the α-bisabolol solution. Patients treated with the bisabolol formulation had a higher rate of complete ulcer healing (25% vs. 0%) and a significant reduction in wound surface area by 73% after 30 days, compared to the control group.(58D) The specific isomer of a-bisabolol was not mentioned.

Alpha-bisabolol for atopic dermatitis and diaper dermatitis

Research has shown that using a corticosteroid-free cream containing starch, glycyrretinic acid, zinc oxide, and bisabolol over a 6-week period resulted in more than a 50% reduction in the severity of atopic dermatitis in children.(59D) The specific isomer of a-bisabolol was not mentioned. Another study about atopic dermatitis used a topical combination of heparin and -/- a-bisabolol (Levomenol). That was more effective than using one of the substances by itself.(60D)

Alpha-bisabolol for epidermal melasma

Epidermal melasma is a hyperpigmentation disorder with limited treatment options. Reductions in the Melasma Area and Severity Index (MASI) scores and total melasma surface area occurred with a cream with a combination of nicotinamide 4%, arbutin 3%, bisabolol 1%, and retinaldehyde 0.05%.(61D) The specific isomer of a-bisabolol was not mentioned.

Alpha-bisabolol is a neuroprotectant

A rat study investigated the effects of the plant-derived pesticide Rotenone, a known environmental neurotoxin linked to Parkinson's disease (PD). Treatment with α-bisabolol was able to prevent the loss of dopaminergic neurons and fibers in the substantia nigra and striatum induced by Rotenone. This neuroprotection was achieved through the reduction of oxidative stress and inflammation by inhibiting IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, iNOS, and COX-2.(62D)

Alpha--bisabolol preserved dopaminergic neurons by attenuating the downregulation of the anti-apoptotic protein Bcl-2, upregulation of the pro-apoptotic protein Bax, and the cleavage of caspases-3 and 9. This terpene is also able to mitigate mitochondrial dysfunction by inhibiting mitochondrial lipid peroxidation, reducing cytochrome-C release, and restoring the levels and activity of ATP and mitochondrial complex I (MC-I).(62D)

Nerolidol

+/- Nerolidol

Cis-Nerolidol

Trans-Nerolidol

Receptor interaction

TRPV1 agonist (68C)

+/- Nerolidol is found in Angelica gigas, Fuscopostia leucomallella, panax ginseng, ginkgo biloba, Illicium verum (Chinese star-anise), and sour orange.(63D)

Cis-Nerolidol is found in Artemisia thuscula and Thulinella chrysantha.(64D)

Trans-Nerolidol is found in Aristolochia triangularis, Rhododendron dauricum, Baccharis dracunculifolia, bitter gourd, and many other sources. This terpene is often used in shampoos, perfumes, detergents, cleansers, and is a food flavoring agent. It also has neuroprotective, anti-fungal, anti-inflammatory, antihypertensive, antioxidant, insect attractant, and herbicidal properties.(65D,66D)

Nerolidol against Bladder Cancer

Cis-nerolidol is cytotoxic to bladder cancer cells through DNA damage induced by endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress, leading to cell cycle arrest. This stress is triggered by cis-nerolidol through β-adrenergic receptor signaling, which activates Protein Kinase A (PKA) and soluble adenylyl cyclase (sAC). These activations result in the release of Ca²+ from the ER into the cytoplasm via ryanodine receptors (RYR channels). Consequently, the accumulation of DNA damage and the induction of ER stress contribute to the anti-cancer effects observed with cis-nerolidol treatment.(67D)

Nerolidol is Antibacterial against Staphylococcus aureus

The antibacterial properties of nerolidol involve the disruption of the cell membrane. Three terpenes were tested, and farnesol was the most effective, followed by nerolidol, then plaunotol.(68D) This study did not indicate whether trans or cis nerolidol was used.

Nerolidol for Fungal infections (Candidiasis) and biofilm

An essential oil from Piper claussenianum is rich in trans-nerolidol. This essential oil reduced the yeast-to-hyphae transition by 81%, and reduced the biofilm formation between 30% after 24 hours of incubation, and 50% after 48 hours of incubation. Fluconazole was found to have a synergistic effect when used with Piper claussenianum essential oil.(69D,70D) The yeast-to-hyphae transition is caused from factors including high temperature (37 °C), high CO2 concentration (~5%), pH 7, nutrition deprivation, and other factors.(71D)

Nerolidol for Ulcer treatment

Nerolidol from Baccharis dracunculifolia was found to have anti-ulcer and gastro-protective properties. Baccharis dracunculifolia has 23% trans-nerolidol. (66D) Doses shown below are from a rat study. Human doses would need to be formulated and tested.

Ethanol-Induced Ulcers: 50 mg/kg (34.20% inhibition, not significant), 250 mg/kg (52.63% inhibition), 500 mg/kg (87.63% inhibition). Omeprazole (positive control) had 50.87% inhibition. (72D)

Indomethacin-Induced Ulcers: 50 mg/kg (34.69% inhibition, not significant), 250 mg/kg (40.80% inhibition), 500 mg/kg (51.02% inhibition). Cimetidine (positive control) had 46.93% inhibition. (72D)

Stress-Induced Ulcers: 50 mg/kg (41.22% inhibition), 250 mg/kg (51.31% inhibition), 500 mg/kg (56.57% inhibition). Cimetidine (positive control) had 53.50% inhibition. (72D)

Nerolidol significantly inhibited ulcer formation in various animal models, showing potential as a therapeutic agent for gastric ulcers.(72D)

Cis-Nerolidol is an antioxidant

Cis-Nerolidol demonstrates hydroxyl radical scavenging activity with an IC50 value of 1.48 mM.(73D) Hydroxyl radicals are highly reactive species that can cause damage to various biomolecules, including proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids. They are implicated in the development of atherosclerosis, cancer, and neurological disorders by reducing disulfide bonds in proteins like fibrinogen.(74D)

Nerol (cis-Geraniol) and

Geraniol (trans-geraniol)

Nerol (cis-Geraniol)

Geraniol (trans-geraniol)

Receptor interaction

Geraniol is an acetylcholinesterase inhibitor with an inhibition at IC50= 98.06 ± 3.9 µM.(75D) Geraniol binds to the CHRM3 receptor (Muscarinic acetylcholine receptor M3).(76D) Geraniol (and Citronellol) is a PPARa and PPARy agonist, and a COX-2 inhibitor.(77D) Geraniol is a TRPV1 putative modulator.(81D) Nerol has no receptor interaction identified, and lacks the research that geraniol has.

Nerol is found in lemongrass, Camellia sinensis and Cymbopogon martinii.(78D)

Geraniol is found in rose oil, palmarosa, citronella, lemongrass, lavender, and coriander oil. (79D)

Geraniol against liver and lung cancer

Geraniol has anti-cancer benefits against liver and lung cancer (HepG2 and A549 cell lines). Geraniol decreased superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase (CAT), and affected the glycolytic pathway in the HepG2 cells; which led to increased oxidative stress and cellular damage.(80D) Geraniol at 400 microM inhibited Caco-2 colon cancer cells by 70% in vitro.(82D)

Geraniol for Alzheimer’s Disease Treatment

Geraniol binds to the CHRM3 receptor (Muscarinic acetylcholine receptor M3) that is a target for the treatment of Alzheimer’s Disease.(83D)

Geraniol is neuroprotective, anti-inflammatory, and antidepressant

A study with mice undergoing chronic unpredictable mild stress and 3 weeks of treatment with geraniol showed a significant reduction in depression related behaviors. Geraniol alleviated neuroinflammation through reducing interleukin-1 beta. This could be from inhibition of nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) pathway activation and regulating nucleotide binding and oligomerization domain-like receptor family pyrin domain-containing 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome expression.(84D)

Is nerol liver toxic or protective?

Nerol can be liver toxic in the occupational setting, or with chronic and long term exposure to it.(78D) A rat study with paracetamol induced liver damage found that nerol at 100 mg/kg reversed the liver damage, including liver enzymes, plasma proteins, antioxidant enzymes, serum bilirubin, lipid peroxidation, and cholesterol.(85D)

Large doses were tested with rats with a range from 2560-9800 mg/kg. 1 of 10 died at the 2560 mg/kg dose, while all 10 died at the 9800 mg/kg dose. Death occurred within 2 days of exposure, with the signs of exophthalmia, hyperflexiveness, restlessness, lethargy and loss of righting reflex.(78D) Human doses are not established, and depending on medical conditions, low doses could cause side effects.

Antimicrobial effects of Geraniol

Geraniol combined with antibiotics increased the Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) against Acinetobacter baumannii in vitro with the following results(86D):

Geraniol + Ceftazidime MIC decreased by >16 to >4,096-fold

Geraniol + Cefepime MIC decreased by 1 to >4,096-fold

Geraniol + Ciprofloxacin MIC decreased by >2 to >4,096-fold

Geraniol + Tigecycline MIC decreased by 4 to >256-fold

Geraniol has bactericidal properties against Escherichia coli, Listeria monocytogenes, and Salmonella enterica.(87D)

Parkinson's Disease and Neuroprotection with Geraniol

A study with mice that had Parkinson’s induced with 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1, 2, 3, 6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP) showed that pre-treatment with geraniol protected against the loss of dopaminergic neurons, and reduced the neurotrophic factors.(88D)

Nerol is an antifungal

Nerol has antifungal properties against Candida albicans. Cell death occurred from mitochondrial membrane depolarization, cytochrome c release, and metacaspase activation.(89D)

Fenchone

Receptor interaction

Fenchone is a 5 HT receptor modulator,(90D) TRPA1 agonist,91D and a COX-2 inhibitor.(92D)

Fenchone has the properties of anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, diuretic, wound-healing, antidiarrheal, antifungal, antinociceptive, and bronchodilator.(97C)

Fenchone is found in fennel, Tetradenia riparia, Pimpinella serbica, (93D) and some strains of cannabis.

Fenchone for IBS-C treatment

Fenchone interacts with the 5HT receptor, which stimulates the intestinal neurons and the vagus nerve to increase gastrointestinal motility and fecal excretion. This is through the cholinergic pathway. Fenchone also positively influenced gut microbiota by increasing beneficial bacteria like Lactobacillus and Blautia, and reducing harmful bacteria such as Enterococcus and Escherichia-Shigella.(90D)

Fenchone is a diuretic

Fenchone has diuretic properties, as shown in a rat study where doses of 200 and 400 mg/kg increased urine output in a dose-dependent manner. Fenchone's significant diuretic potential is comparable to furosemide.(94D) Human doses need to be established. Pre-existing conditions, such as heart failure, would need caution using fenchone, as well as combining that with prescription medications, especially diuretics.

Fenchone is an anti-inflammatory

Fenchone is a COX-2 inhibitor, and its anti-inflammatory effects also lowered iNOS, IL-17, IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α. (92D)

Fenchone may have stimulant or “Sativa” properties from its diuretic effects and interaction with 5HT receptors.

Camphene

-/- Camphene

+/- Camphene

(+/-)- Camphene

Receptor interaction

The interaction of camphene with TRPV3 is not well-established; camphor, a related terpene,

is a known TRPV3 agonist.(95D)

(-)- Camphene is found in Artemisia xerophytica, and Salvia officinalis.(96D)

+/- Camphene is found in Magnolia officinalis and Fuscopostia leucomallella.(97D)

(+/-)- Camphene is found in cannabis, Otanthus maritimus, Rhododendron dauricum.(98D)

Camphene for cardioprotection?

A rat study showed that camphene protected cardiomyocytes against ischemic/reperfusion (I/R) injury to the heart. This is from reducing myocardial infarct size and cell death after reperfusion, reduces oxidative stress, and decreases ferroptosis.(99D)

Camphene is an antioxidant

Camphene has antioxidant properties. It can reduce oxidative stress in relation to protecting the heart from damage during ischemia/reperfusion injury.(99D) Camphene can be used to make products (Camphene-Based Thiosemicarbazones) that have strong antioxidant properties that scavenge peroxyl radicals.(1E) Peroxyl radicals attack nearly all types of biological molecules (such as proteins, lipids, and sugars), and play a role in the development of diabetes, Alzheimer's disease, atherosclerosis, and autoimmune disorders.(2E)

Cedrol